How to Burn Fat and Why You Shouldn’t – 180 Degree Health

By Danny Roddy, author of

The Peat Whisperer

Traversing through the blogosphere reveals much text, but little art. This is, until you stumble upon the site of low-carb sage Petro Dobromylkyj. Similar to da Vinci’s “David” or Shakespeare’s

Hamlet, Petro’s exudes extraordinary vision. One doesn’t have to read past the header for the first glimpse of his contribution to The Great Work:

“

You need to get your calories from somewhere should it be from carbohydrate or fat?” —

Petro Dobromylkyj

If I was forced to interpret Petro’s poem, I would say that he’s trying to tell us that carbohydrates reassure men that they can be masters of their own reality—but then turns around and says that actually, reality is not real.

Another interpretation, which sounds less plausible, could be that one must decide where to obtain their fuel from:

carbohydrate or fat.

While the blogosphere has been polluted with the idea that “

using fat as fuel” is somehow

more desirable than glucose, in this article, I intend to describe how

lipolysis (i.e., the liberation of free fatty acids into the blood)

is a feature of stress, disease and aging.

Lazy Reader Summary:

- Glucose and oxygen, which are substrates for efficient energy production, are the two most basic anti-stress substances

- Carbon dioxide (CO2), which is produced under the influence of active thyroid hormone, is needed to use glucose and oxygen efficiently

- Stress liberates free fatty acids (non-esterified fatty acids or NEFA) into the blood for use as fuel

- The use of free fatty acids as fuel supplies less carbon dioxide than the complete oxidation of glucose

- The liberation of free fatty acids into the blood interrupts the use of glucose in the short- and long-term

- Over time, free fatty acids damage the cell’s highly evolved ability to produce oxidative energy (i.e., glucose to carbon dioxide)

- Those with obesity and diabetes have markers suggestive of stress and the production of energy through inefficient glycolysis (i.e. glucose to lactic acid):

- Increased blood levels of adrenaline

- Increased blood levels of cortisol

- Increased blood levels of lactate

- Reduced respiratory quotient (i.e., less carbon dioxide produced)

- Increased reliance on free fatty acids as fuel

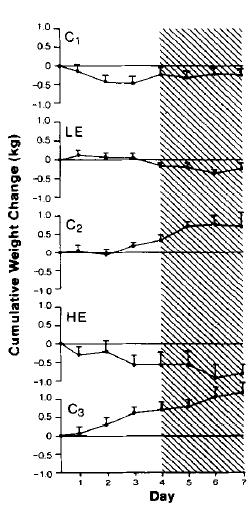

- Decreased thermogenesis upon food ingestion (especially carbohydrate)

- Low-carb high-fat (LCHF) diets may have short-term therapeutic effects (e.g., if one loses weight or reduces allergenic/inflammatory substances that were being consumed previously)

- In terms of reversing the degenerative effects of stress, LCHF diets are mostly counter-productive as they simulate the stress metabolism

- People lose fat on diets that aren’t LCHF

- Calcium, fructose, aspirin, niacinamide, and the fat soluble vitamins are therapeutic aids to restore normal glucose metabolism

Anti-Stress Factors: Glucose, Oxygen & Carbon Dioxide

In my

first guest post on 180 Degree Health we chatted about stress increasing our energy requirements. In this context,

glucose and oxygen,

which are substrates for efficient energy production,

can be thought of as the two most basic anti-stress factors.

We also briefly went over carbon dioxide’s role in stress and how the complete oxidation of

glucose (i.e., mitochondrial respiration)

supplies more carbon dioxide than the oxidation of fat.

In addition to allowing cells, tissues, and organs to absorb oxygen, carbon dioxide has some other interesting qualities:

- Carbon dioxide is an anti-inflammatory, opposing the production of pro-inflammatory lactic acid

- Carbon dioxide has been referred to as a “cardinal adsorbent,” meaning that it has a powerful controlling influence in restoring order and coherence to the entire organism

- Carbon dioxide maintains cellular ion gradients (i.e., so that the cell retains far more potassium than sodium and is able to excrete calcium while binding magnesium)

Carbon Dioxide? Big Whoop… Turn me into a fuggin’ Fat-Burning Beast Roddy!

Free Fatty Acids In The Stress Response

As I’ve mentioned previously, Hans Selye first introduced the concept that in response to a wide range of stressors (e.g., darkness, low blood sugar, toxic drugs, loud noises, forced exercise, etc.), the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis is invariably activated and there is an increase in cortisol secretion.

This is an adaptive,

life-saving reflex in the short-term, but when the exposure to stressors is

excessive or

prolonged,

degenerative processes are set in motion, which is ultimately a result

of failing adaptive mechanisms and

inability to generate sufficient energy.

Additionally, Selye often pointed out that 1) stress is unavoidable and 2) the impact of stress is proportional to how we perceive it (i.e., stress before a gnarly hot make out is not the same as being hungry and going without food for 24 hours,

however both stressors would transiently increase energy requirements).

Meeting these energy demands requires the efficient use of glucose and oxygen by living cells. A deficiency of either one requires a “

higher functioning” of our adaptive stress hormones to compensate for the reduced energy supply. A hormone central in this adaptive response is

adrenaline.

A healthy person is able to store a meaningful amount of glucose in the form of hepatic glycogen (the muscles use their glycogen for themselves). When a stress is encountered that can’t quickly be overcome, adrenaline, which is released from the adrenal glands (and noradrenaline to some extent, which is predominantly released from the sympathetic nerve endings), stimulates the breakdown of hepatic glycogen, releasing stored glucose into the blood.

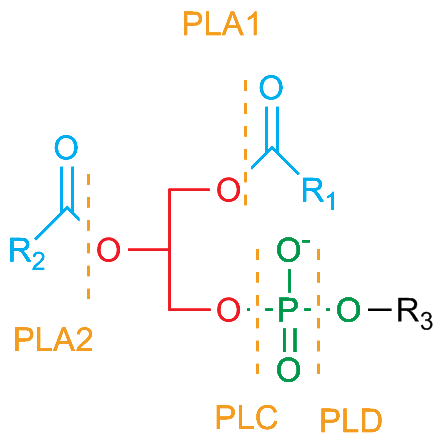

At the same time, adrenaline (along with glucagon, which has an inverse relationship with insulin) stimulates fatty acid mobilization, which serves as an alternate fuel source to glucose, from adipose tissue and, in a vicious cycle, activates the HPA axis, amplifying the stress metabolism.

Selye notes in his book

The Stress of Life that blood levels of free fatty acids,

similar to cholesterol, is a marker for stress:

“The elevation in certain blood lipid substances, such as cholesterol and free fatty acids, are comparatively simple to estimate, although they do require a chemical laboratory. Rises in STH, glucagon, insulin and prolactin are not only more difficult to determine, but also less reliable indicators of stress reactions in man.” – Hans Selye

So “stress” releases fat into the blood… Big deal… Roddy…

In 1963 P.J. Randle and his colleagues described the inhibition of the use of glucose by elevated levels of free fatty acids as an immediate physiological phenomenon. For example, brief bouts of intense exercise or fasting will raise free fatty acid levels, which will thereafter be used for fuel in preference to glucose, until glucose can be supplied (insulin suppresses the use of free fatty acids).

Over time, however, the chronic exposure to free fatty acids leads to a myriad of toxic effects,

such as damage to the energy generating apparatuses of cells and an increase in the prostaglandin modulation of the aromatase enzyme, which creates new estrogen. These are just some of the many long-term consequences.

As evidence for the role of free fatty acids in these long-term degenerative conditions, consider some of the common features between obesity and diabetes:

- Reduced respiratory quotient (i.e. less carbon dioxide is produced)

- Increased levels of lactate in the blood of diabetics (i.e., energy production through glycolysis instead of our high evolved oxidative metabolism)

- Decreased heat production (thermogenesis) upon the ingestion of food, especially carbohydrate

- Increased levels of free fatty acids (generally)

- Increased levels of adrenaline, which initiates the stress response

- Increased levels of cortisol, which sustains the stress response

Is Low Carb a Tool? Possibly Maybe, Probably Not

In a recent article it was mentioned that HFLC diets are simply a “

tool in the toolbox” for those who are “

metabolically broken”. More specifically that ‘

if you are insulin resistant, have fat in your belly or not sleeping well, then you should limit your carbohydrate intake below 50-110g…’

To recap, “stress” is anything that increases our energy demands, and glucose and oxygen are the basic substrates needed for efficient energy production.

A HFLC diet aims to “treat” poor glucose tolerance (

a sign of stress) by replacing carbohydrate with fat; however,

the excessive oxidation of fats (

especially when polyunsaturated)

impairs the cell’s ability to oxidatively metabolize glucose to carbon dioxide, water, and hydrogen.

In this context, a HFLC diet can be conceived as a diet that

activates the stress metabolism.

Uhhh… Yeah whatever Roddy, I lost fat and I feel fuggin’ so badass on HFLC. Fat FTW!!1

Losing weight is part of the equation, and any diet that induces weight loss is likely to increase metabolic efficiency. However, there may be a couple of reasons for the initial “success” of low-carbers:

- As Andrew Kim has pointed out, insulin resistance is not necessarily induced on hypocaloric HFLC diets because fatty acid oxidation keeps up with fatty acid mobilization. In other words, you are burning through fat at an accelerated rate.

- As Matt has written about in Catecholamine Honeymoon, some stress hormones have anti-depressant and anti-inflammatory actions. Similar to fasting, this can provide a false sense security with one’s health (monitoring pulse and body temperature can help one avoid this problem).

- LCHF diets exclude numerous foods that could cause inflammation or allergies.

Look, Roddy, I get it, but if I don’t use fat as fuel, I will never lose any weight. Everyone knows that.

“Healthy” fat loss is most likely a combination of keeping the metabolic rate up, consuming a nutrient-dense diet, and getting sufficient calories per your needs (e.g., stress and activity levels) – the basic message of

Diet Recovery 2 and most of the material on this site.

Suppressing lipolysis doesn’t mean that you will never burn fat for energy. In fact, large skeletal muscles prefer saturated fats as a source of fuel while at rest, as does the heart’s myocardium.

If you take away anything from this article, let it be that the hormones that mobilize fatty acids are the same hormones involved in the degenerative effects of stress.

These hormones have short-term protective qualities (i.e., survival), but long-term negative effects such as immune system suppression (cortisol dissolves the thymus and renders us susceptible to infections and food allergies) and thyroid inhibition (cortisol interrupts the conversion of thyroxine to triiodothyronine).

Practical Application: Niacinamide, Aspirin & Fructose

Simple, yet effective, strategies like consuming more carbohydrate than protein (i.e. protein is insulinogenic and alone uncomfortably lowers blood sugar), avoiding polyunsaturated fats – like corn oil just to name one common source (which damage the energy producing apparatuses of the cell and decrease the rate of energy generation), and, for those who have blood sugar control issues, consuming fat, protein, and carbohydrate together can help to achieve steady blood sugar levels throughout the course of a day.

Niacinamide (not niacin or nicotinic acid) and aspirin (with vitamin K) both suppress lipolysis and can be considered rational treatments for those with advanced cases of insulin resistance.

Despite the irrelevant “

evolutionary” interpretation of fructose, in the context of supporting the known factors that influence energy production, fructose (along with glucose):

- Improves insulin sensitivity

- Bypasses and activates key steps in glycolysis that are inhibited in people with poor glucose tolerance

- Restores diet-induced thermogenesis and carbon dioxide levels to near normal more than glucose alone does

Increased parathyroid hormone correlates with insulin resistance and can be suppressed with enough dietary calcium, vitamin D, and vitamin K. Fructose, by depleting intracellular phosphate, decreases blood parathyroid hormone levels, too.

References: