It’s that special time of year, folks!

Yes, step right up ladies and gentlemen, and welcome to the

2014 Annual Red Meat Causes Cancer Wankfest!

Never heard of the ARMCCW, you say? No idea what it involves?

Well, let me tell you all about it, then.

Every year, the deluded sods that largely comprise the nutritional epidemiology community partake in a ritual where they

“associate”

red meat with cancer incidence. Sometimes it’s overall cancer, other

times they zero in on a particular malignancy such as colon, rectal,

prostate, or pancreatic cancer.

Sometimes, they get a wee bit depressed by the whole cancer thing, so instead temporarily try their hand at

“associating”

read meat with heart disease. But cancer is where the real action is at

when it comes to bashing red meat, so that’s where the epidemiological

shysters tend to focus their energy.

Before we learn which cancer is the star of 2014’s ARMCCW, let’s take

a quick look behind the scenes to see exactly how this farce operates.

The Sham, and How It Works

I’ve written about this appalling charade before

here and

here, so long-time readers probably already know where this is heading. And so I’ll try to be brief(ish).

Basically, epidemiologists dredge large confounder-prone prospective

studies, jump all over a pathetically weak statistical association

between meat and their malignancy of choice, then carry on like it’s

causal.

It’s a prolific scam, because they can always count on red meat to show an association with cancer risk.

Not because red meat is carcinogenic. Unless you regularly consume

charred or overcooked red meat, it isn’t. Red meat, in fact, is the

healthiest, most nutrient-dense food known to mankind. That’s why our

ancestors often placed themselves in great physical danger to get at it.

What, you think they would’ve risked life and limb to get fresh red

meat if their nutritional needs could’ve been met by wild spinach and

acorns?

Yeah, right. Only vegetarians believe absurd shit like that.

So why, then, would meat ever be associated with cancer in these epidemiological studies?

Because, invariably, people who eat the most red meat in these

studies also have the highest rate of truly unhealthy behaviours like

smoking, low physical activity, excess alcohol consumption, excess

caloric consumption, and on and on and on.

Why would people who eat the most red meat exhibit poorer overall health practices?

Because people who care less about their health don’t just ignore perfectly sensible health messages like

“Don’t Smoke”,

“Do Regular Exercise” and

“Eat Your Veggies”. They also ignore patently idiotic health messages with no foundation in reality, such as

“Avoid Red Meat”!

And so people who smoke more, exercise less, hit the booze more

often, eat a poorer diet overall, have a higher bodyweight, etc, etc,

also tend to eat more red meat.

These people, not surprisingly, will be at higher risk of cancer. And so red meat becomes guilty by association.

If the nutritional epidemiologists responsible for these studies

weren’t so deluded, they’d stop right there, and admit their work

provides nothing but statistical associations of unknown origin. To

establish the origin of those associations as causal, they’d need to

conduct randomized clinical trials comparing groups of subjects randomly

assigned to diets containing red meat, or to diets not containing red

meat.

They’d let these trials run for a good stretch of time, then at the

end tally up the number of people who got cancer in each dietary group.

If the red meat group had a significantly higher incidence of cancer

during the trial, then we’d have pretty strong grounds for believing red

meat causes cancer. Of course, we’d need follow-up RCTs to replicate

these results and confirm they weren’t just a “fluke” finding.

But epidemiologists don’t like RCTs, and here’s why:

–The results of quality RCTs have an annoying habit of showing

epidemiological findings to be utter bollocks. An excellent example of

this is the

“Whole-Grains are Good for You!” sham.

Epidemiological studies supporting this terribly mistaken notion are a

dime a dozen, but every time an RCT (both the parallel arm and crossover

variety) has examined this issue, the whole-grain group has fared

worse. Because that flies in the face of all the

“healthy whole-grain”

propaganda that we’ve been bombarded with by health ‘experts’ and

‘authorities’, those ‘experts’ and ‘authorities’ do what most people

heavily vested in a false belief do:

Evade reality.

They simply pretend the RCTs don’t exist, and completely ignore them

when writing and talking about the issue. Instead, they enthusiastically

cite all the epidemiological studies showing an

“association”

between whole grain cereals and reduced disease risk (I’ve discussed

this disgraceful phenomenon thoroughly but concisely in my most recent

book

Whole Grains, Empty Promises).

–RCTs are expensive, and they involve a lot of work. And even the

best RCTs are usually only good for a handful of journal articles.

Epidemiological studies, on the other hand, are like popular prime time

soap operas and reality shows: A lucrative, never ending bounty of

bullshit.

In epidemiological studies, you don’t need to randomize people, you

don’t need to give them detailed instruction, and you don’t need to take

any measures to encourage or monitor compliance with any intervention.

Shit, you don’t even need an intervention!

In an epidemiological study, you simply recruit a bunch of people,

give them a questionnaire at the start and, if you can be assed, a

follow-up survey every few years.

When the forms come back in the mail, you fire up the computer, run some data analyses and – bingo! – you’ve got a paper!

Or, more likely, you’ll have twenty papers. Or if you’re from the

Harvard Public School of Health, you’ll eventually have dozens upon

dozens of papers from the one study!

Because they’re far less sophisticated and hence easier to conduct,

epidemiological studies can involve far larger numbers of subjects. In a

world where B-I-G things – be they incomes, buildings, boats, or boobs –

tend to impress more people, studies involving tens of thousands and

sometimes hundreds of thousands of subjects have a giddying effect on

researchers and journalists.

Also, because there’s no intervention, you aren’t forced to focus on a

specific health issue, which is the case with an RCT. You can’t, for

example, conduct an RCT testing the effect of red meat intake on cancer,

then use the data from that RCT to also publish a paper on the effect

of blueberry intake on haemorrhoid incidence. The design of the study

just won’t allow it.

But you can do exactly that with an epidemiological study in which

you have intake data for dozens of foods and questionnaires that ask

about the incidence of a whole host of health ailments. Never mind that

this intake data is self-reported and therefore well-established to be

of highly dubious quality – epidemiologists certainly don’t. They just

go ahead and take it seriously, crunch the numbers, and spit out papers

one after the other.

For researchers and academics, there’s a lot of prestige attached to

being a prolific author of published, peer-reviewed papers. The more the

merrier. And a large nutritional epidemiological study offers a

limitless opportunity for the researchers involved to accumulate

published titles to their names. Don’t believe me? Fine, enter the

following into Pubmed and see what happens:

“Nurses’ Health Study”, “Harvard Physicians’ Study”, “Framingham Study”, “INTERHEART” …

It’s the old quantity versus quality scenario in full effect. RCTs

might be considered the gold standard of scientific research, but we

live in a world where fiat currencies rule the roost. And like the fifty

dollar note in your pocket that is nothing but ink on a bit of paper

(actual worth of ink + paper = a few cents), all is not what it seems

with epidemiology.

The 2014 Wankfest

ARMCCW 2014 involves the

Nurses’ Health Study II, emanating from Ground Zero of epdemi-hogwash: The Harvard School of Public Health.

It’s a hallowed place, Harvard. Which, sadly, gives the nonsense

emanating from their nutritional epidemiologists a veneer of prestige

and respectability. But make no mistake: Underneath that smart-looking

polished mahogany exterior lies the same old confounder-prone rot.

Soooo … what cancer is taking centre stage at this year’s ARMCCW?

Breast cancer.

The researchers claim

“each serving per day increase in red meat was associated with a 13% increase in risk of breast cancer.”

They further claim:

“When this relatively small relative risk is applied to breast

cancer, which has a high lifetime incidence, the absolute number of

excess cases attributable to red meat intake would be substantial, and

hence a public health concern. Moreover, higher consumption of poultry

was related to a lower incidence of breast cancer in postmenopausal

women. Consistent with the American Cancer Society guidelines,

replacement of unprocessed and processed red meat with legumes and

poultry during early adulthood may help to decrease the risk of breast

cancer.”

What this shows is that, even if you work at The World’s Most

Prestigious University!™, you can still be utterly clueless about

scientific reality. Modern humans have constructed a societal structure

in which bullshit can flourish and wield great influence, and

nutritional epidemiology thrives as a result.

Before I explain in more detail why the association between red meat

and breast cancer doesn’t even begin to qualify as causal, I’d like to

address the observation that

“higher consumption of poultry was related to a lower incidence of breast cancer in postmenopausal women.”

This is hardly the first epidemiological study to notice that poultry and/or fish are

“associated” with improved health outcomes.

Why?

For the very same reason that red meat is

“associated” with

poorer outcomes: Health conscious individuals who smoke less, exercise

more, don’t binge drink etc, etc, etc are more likely to eat white meat

instead of red. Because that’s what all the public health messages and

poncey “wellness” magazines they read tell them to do.

Anyway, let’s look at the

study itself.

It involved 88,803 premenopausal women from the Nurses’ Health Study II who completed a “semi-quantitative” food frequency

questionnaire

in 1991, 1995, 1999, 2003, and 2007 asking about usual dietary intake

and alcohol consumption for the previous 12 months. The researchers also

asked about things like weight, family history of breast cancer,

smoking, race, age at menarche, parity (ie, number of children they’d

given birth to), and oral contraceptive use.

They followed the women for an average of 20 years, during which time 2,830 cases of breast cancer were documented.

When carrying out their pre-determined task of linking red meat to

cancer risk, the researchers divided the women up into 5 categories

according to their red meat consumption. And sure enough, as red meat

consumption went up, so too did breast cancer risk.

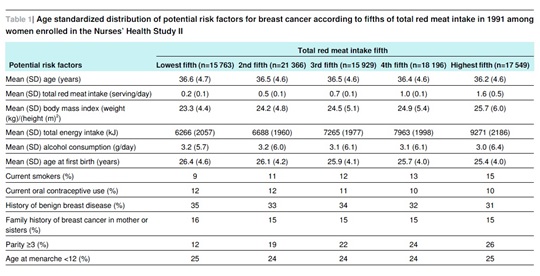

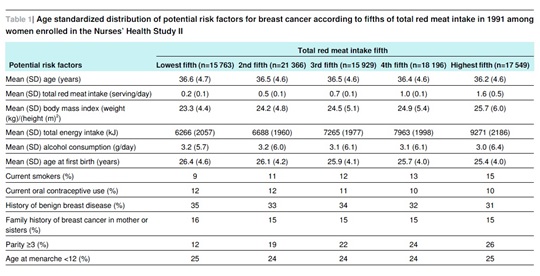

But take a look at Table 1 from the study below:

You can see that as red meat consumption went up, the number of smokers

also went up in a perfect linear fashion. The group with the highest red

meat intake had 67% more smokers.

Gee, you think that might increase their breast cancer risk?

Naaaah…

Now, if smoking went up in step with red meat consumption, you’d

expect other unhealthy behaviours including physical inactivity, junk

food consumption, recreational drug use, and erratic sleep habits to

increase along with red meat consumption. Despite their overwhelming

importance, the researchers didn’t see fit to ask about and/or include

these variables in Table 1.

But we do know as red meat intake rose, so too did total caloric consumption and BMI.

But that’s not all. Take a look at the second last line, the one that begins with “

Parity ≥3 (%)“.

The figures that follow are the percentage of women in each group who

reported giving birth to 3 or more children. Again, as red meat intake

goes up, so too does the number of women reporting having 3 or more

kids. The difference is quite pronounced – those with the highest red

meat intake were more than twice as likely to have had 3 or more full

term pregnancies.

Why does this matter?

Because parity is an important risk factor for breast cancer. While

giving birth to one’s first child at a young age has been consistently

associated with a lower risk of late onset cancer, the risk of early

onset cancer (i.e. the type of cancer that would be more likely to occur

during a study like this)

rises with each and every pregnancy a woman has.

I won’t go into the physiological reasons for this – if you’re

interested consult Dr Google and you’ll find plenty of information. All I

will point out here is the bleeding obvious: The number of children a

woman bears has little if anything to do with the amount of red meat she

eats and everything to do with the amount of fornication (sans

effective contraception) she engages in when ovulating.

Fucking duh (evidently, the epidemiologists at The World’s Most

Prestigious University!™ need a little more basic sex education).

But again, blaming clearly established risk factors like smoking and

higher parity for breast cancer doesn’t sit too well with the anti-red

meat agenda. Yep, this is the Blame Red Meat Wankfest, gotta get with

the festive spirit!

But how do you do that when starkly contrasting smoking and parity rates threaten to ruin the party?

Easy.

You pull out the favourite prop of epidemiologists all around the world – the statistical wand!

You take this pretty pink little wand, you wave it all about, and when you finish you pretend you have magically

“adjusted” for such pesky confounders as smoking and parity!

The only way you can truly adjust for anything is to take your

subjects and randomly assign them to either an intervention (red meat)

or control (no red meat) group. In other words, you do a randomized

clinical trial (RCT). The randomization process negates the problem that

plagues nutritional epidemiological studies – confounding. That’s

because randomly assigning people to the intervention and control groups

means people with unhealthy habits are just as likely as people with

healthy habits to end up in the no-red meat group. And vice versa.

But as we’ve already seen, epidemiologists hate RCTs. So what they do

instead is engage in an Emperor-has-no-clothes charade where they use

formulas – derived Ponzi-style from other confounder-prone

epidemiological studies – to statistically

“adjust” for confounding variables. They honestly believe they can tease out the effect of these variables

after the fact.

You and I might call this delusional. Epidemiologists call it

“multivariate analysis.”

For a sterling example of how multivariate analysis routinely falls flat on its face, I refer you back to the

“whole-grains are healthy!”

hyperbole. Again, really big epidemiological studies whose crude data

was carefully massaged, uh, I mean, adjusted, show wonderfully lower

rates of morbidity and mortality among those eating the most

whole-grains.

But when the theory is put to the test in randomized clinical trials,

those assigned to eat more whole-grains or cereal fibre (the exact

component of whole-grains we are supposed to believe is wonderfully

healthy) are the ones who suffer higher rates of morbidity and

mortality. Again, if you want a detailed but easy-to-read breakdown of

this phenomenon, grab yourself a copy of

Whole Grains, Empty Promises

(all proceeds support the International Ramone Foundation, a non-profit

organization devoted to keeping my dog happy, well-fed, and built like a

brick outhouse).

Remember, quality (RCTs) versus quantity (epidemiology).

So there it is, folks. Now you know all about the Annual Red Meat

Causes Cancer Wankfest, and how it works. Think of an Olympic Torch, but

one that spouts bullshit instead of flames. It travels the world,

getting handed from one anti-red meat group to another, passing with

unusual frequency through Boston, Massachusetts.

One last thing before I sign off. I’ve actually made this point

before, but because a lot of people are dumb as shit I need to make it

again. I sound like I have a very low opinion of epidemiology and … well

… I do. The amount of utter bullshit that is propped up and made to

look like science as a result of garbage epidemiological studies is

truly astounding. And quite disheartening, when you think of all the

unnecessary misery and mortality that has resulted from totally missing

the boat on what really causes things like cancer and heart disease.

It’s an absolute disgrace.

However, I’m not against

all epidemiology. The link between

cigarette smoking and lung cancer owes much to epidemiology. Ditto with

infectious disease or food poisoning outbreaks – epidemiology allows

researchers to determine key similarities among those afflicted and

track down the source so they can begin containing the problem as

quickly as possible.

It’s when epidemiology turned its attention to dietary intake and

chronic disease that things really turned to crap. Epidemiology is well

suited to situations like those I listed above, because the factors

being studied are so clear cut and the mechanisms so obvious, there’s

far less doubt about the relationship that intertwines them all. For

example, it doesn’t take a brain (or lung) surgeon to realize the

possibility that smoking cigarettes and filling your lungs with noxious

fumes for years on end might cause lung cancer.

Nor do you need to be particularly bright to realize what might be

going on when people all over the country suddenly start showing up at

emergency wards vomiting their guts out, and subsequent investigation

reveals that the one thing they all have in common is that they ate a

particular brand of pre-packaged raw salad, emanating from a single food

processing plant in Boise, Idaho.

But when epidemiology experienced these early successes, developed

way too much of a cocky swagger, and figured it would turn its attention

to the link between diet and chronic disease … that’s the point at

which it crossed the line from utilitarian and helpful and instead

started venturing into downright delusional territory.

Not only are the confounding variables

involved in diet and lifestyle too numerous for any non-omnipotent

creature (i.e. any human researcher) to fully account for, but it’s also

well established that misreporting in dietary questionnaires is not the

exception but the norm.

The continual and unavoidable presence of confounding and

misreporting in population-based studies is why most nutritional

epidemiology is

absolute bullshit.

Don’t base your health decisions on absolute bullshit.

The favoured drink of epidemiologists worldwide.

The favoured drink of epidemiologists worldwide.

author has no relationship whatsoever with the meat industry – nor any

other food-related industry – aside from that of paying consumer.

—

Anthony Colpo is author of

The Fat Loss Bible, The Great Cholesterol Con and

Whole Grains, Empty Promises.

Copyright © Anthony Colpo.

Disclaimer: All content on this web site is provided for information

and education purposes only. Individuals wishing to make changes to

their dietary, lifestyle, exercise or medication regimens should do so

in conjunction with a competent, knowledgeable and empathetic medical

professional. Anyone who chooses to apply the information on this web

site does so of their own volition and their own risk. The owner and

contributors to this site accept no responsibility or liability

whatsoever for any harm, real or imagined, from the use or dissemination

of information contained on this site. If these conditions are not

agreeable to the reader, he/she is advised to leave this site

immediately.