I feel sorry for insulin. Insulin has been

bullied and beaten up. It has been cast as an evil hormone that should

be shunned. However, insulin doesn't deserve the treatment it has

received.

Insulin: A Primerbullied and beaten up. It has been cast as an evil hormone that should

be shunned. However, insulin doesn't deserve the treatment it has

received.

Insulin is a hormone that regulates the levels of sugar in your

blood. When you eat a meal, the carbohydrate in the meal is broken down

into glucose (a sugar used as energy by your cells). The glucose

enters your blood. Your pancreas senses the rising glucose and releases

insulin. Insulin allows the glucose to enter your liver, muscle, and

fat cells. Once your blood glucose starts to come back down, insulin

levels come back down too. This cycle happens throughout the day. You

eat a meal, glucose goes up, insulin goes up, glucose goes down, and

insulin goes down. Insulin levels are typically lowest in the early

morning since it's usually been at least 8 hours after your last meal.

Insulin doesn't just regulate blood sugar. It has other effects as well. For example, it stimulates your muscles to build new protein (a process called protein synthesis). It also inhibits lipolysis (the breakdown of fat) and stimulates lipogenesis (the creation of fat).

It is the latter effect by which insulin has gotten its bad

reputation. Because carbohydrate stimulates your body to release

insulin, it has caused some people to argue that a diet high in

carbohydrate will cause you to gain fat. Their reasoning, in a

nutshell, goes like this:

High Carbohydrate Diet -> High Insulin -> Increased

Lipogenesis/Decreased Lipolysis -> Increased Body Fat -> Obesity

Using this same logic, they argue that a low carbohydrate diet is

best for fat loss, because insulin levels are kept low. Their logic

chain goes something like this:

Low Carbohydrate Diet -> Low Insulin -> Decreased Lipogenesis/Increased Lipolysis -> Decreased Body Fat

However, this logic is based on many myths. Let's look at many of the myths surrounding insulin.

MYTH:A High Carbohydrate Diet Leads to Chronically High Insulin Levels

FACT:Insulin Is Only Elevated During the Time After a Meal In Healthy Individuals

One misconception regarding a high carbohydrate intake is that it

will lead to chronically high insulin levels, meaning you will gain fat

because lipogenesis will constantly exceed lipolysis (remember that fat

gain can only occur if the rate of lipogenesis exceeds the rate of

lipolysis). However, in healthy people, insulin only goes up in

response to meals. This means that lipogenesis will only exceed

lipolysis during the hours after a meal (known as the postprandial period).

During times when you are fasting (such as extended times between

meals, or when you are asleep), lipolysis will exceed lipogenesis

(meaning you are burning fat). Over a 24-hour period, it will all

balance out (assuming your are not consuming more calories than you are

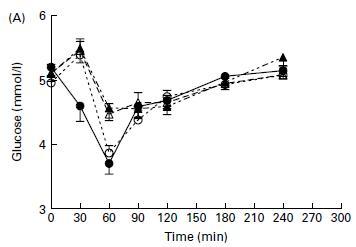

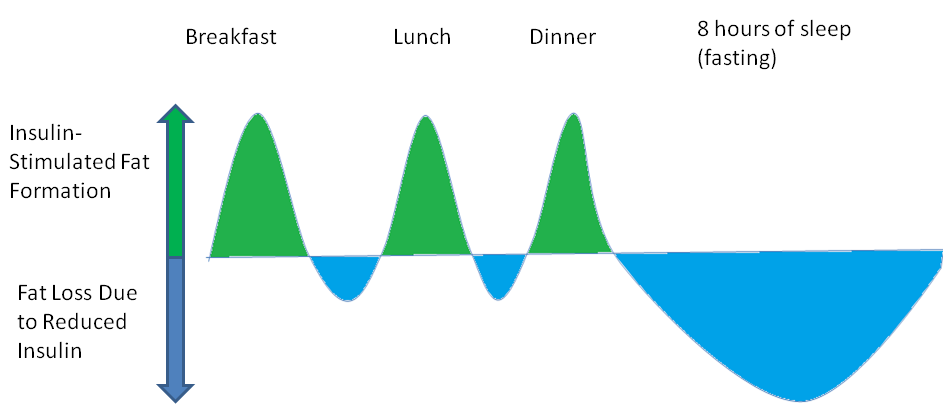

expending), meaning you do not gain weight. Here's a graph showing how

this works:

After

meals, fat is deposited with the help of insulin. However, between

meals and during sleep, fat is lost. Fat balance will be zero over a

24-hour period if energy intake matches energy expenditure.

meals, fat is deposited with the help of insulin. However, between

meals and during sleep, fat is lost. Fat balance will be zero over a

24-hour period if energy intake matches energy expenditure.

the lipogenesis occuring in response to a meal. The blue area

represents lipolysis occuring in response to fasting between meals and

during sleep. Over a 24-hour period, these will be balanced assuming

you are not consuming more calories than you expend. This is true even

if carbohydrate intake is high. In fact, there are populations that

consume high carbohydrate diets and do not have high obesity rates, such

as the traditional diet of the Okinawans. Also, if energy intake is lower than energy expenditure, a high carbohydrate diet will result in weight loss just as any other diet.

MYTH: Carbohydrate Drives Insulin, Which Drives Fat Storage

FACT: Your Body Can Synthesize and Store Fat Even When Insulin Is Low

One of the biggest misconceptions regarding insulin is that it's

needed for fat storage. It isn't. Your body has ways to store and

retain fat even when insulin is low. For example, there is an enzyme in

your fat cells called hormone-sensitive lipase (HSL). HSL helps break

down fat. Insulin suppresses the activity of HSL, and thus suppresses

the breakdown of fat. This has caused people to point fingers at

carbohydrate for causing fat gain.

However, fat will also suppress HSL even when insulin levels are low.

This means you will be unable to lose fat even when carbohydrate intake

is low, if you are overeating on calories. If you ate no carbohydrate

but 5,000 calories of fat, you would still be unable to lose fat even

though insulin would not be elevated. This would be because the high

fat intake would suppress HSL. This also means that, if you're on a low

carbohydrate diet, you still need to eat less calories than you expend

to lose weight.

Now, some people might say, "Just try and consume 5000 calories of

olive oil and see how far you get." Well, 5000 calories of olive oil

isn't very palatable so of course I won't get very far. I wouldn't get

very far consuming 5,000 calories of pure table sugar either.

MYTH: Insulin Makes You Hungry

FACT: Insulin Suppresses Appetite

It is a well known fact that insulin acutely suppresses appetite. This has been demonstrated in dozens and dozens of experiments. This will be important when we talk about the next misconception...

MYTH: Carbohydrate Is Singularly Responsible for Driving Insulin

FACT: Protein Is a Potent Stimulator of Insulin Too

This is probably the biggest misconception that is out there.

Carbohydrates get a bad rap because of their effect on insulin, but

protein stimulates insulin secretion as well. In fact, it can be just

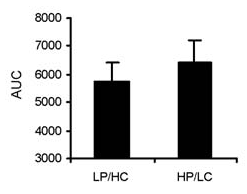

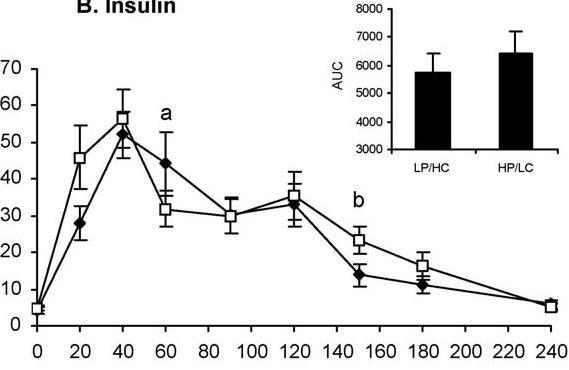

as potent of a stimulus for insulin as carbohydrate. One recent study compared the effects of two different meals on insulin.

One meal contained 21 grams of protein and 125 grams of carbohydrate.

The other meal contained 75 grams of protein and 75 grams of

carbohydrate. Both meals contained 675 calories. Here is a chart of

the insulin response:

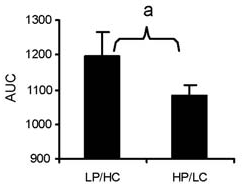

Now here's a chart of the blood sugar response:

You can see that, despite the fact that the blood sugar response was

much higher in the meal with more carbohydrate, the insulin response

wasn't higher. In fact, the insulin response was somewhat higher after

the high protein meal, although this wasn't statistically significant.

Some people might argue that the "low-carb" condition wasn't really

low carb because it had 75 grams of carbohydrate. But that's not the

point. The point is that the high-carb condition had nearly TWICE as

much carbohydrate, along with a HIGHER glucose response, yet insulin

secretion was slightly LOWER. The protein was just as powerful at

stimulating insulin as the carbohydrate.

I can also hear arguments coming like, "Yeah, but the insulin

response is longer and more drawn out with protein." That wasn't true

in this study either.

You can see in the chart that there was a trend for insulin to peak

faster with the high protein condition, with a mean response of 45 uU/mL

at 20 minutes after the meal, versus around 30 uU/mL in the high carb

condition.

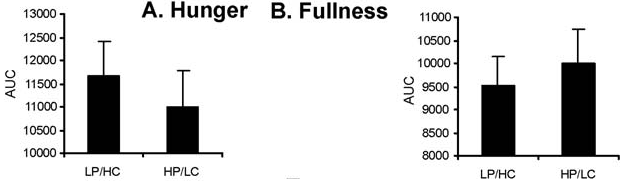

This tendency for a higher insulin response was associated with a

tendency towards more appetite suppression. The subjects had a tendency

towards less hunger and more fullness after the high protein meal:

Comparison of low protein, high carb and high protein, low carb meals and their effects on hunger and fullness

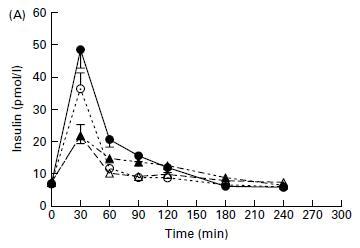

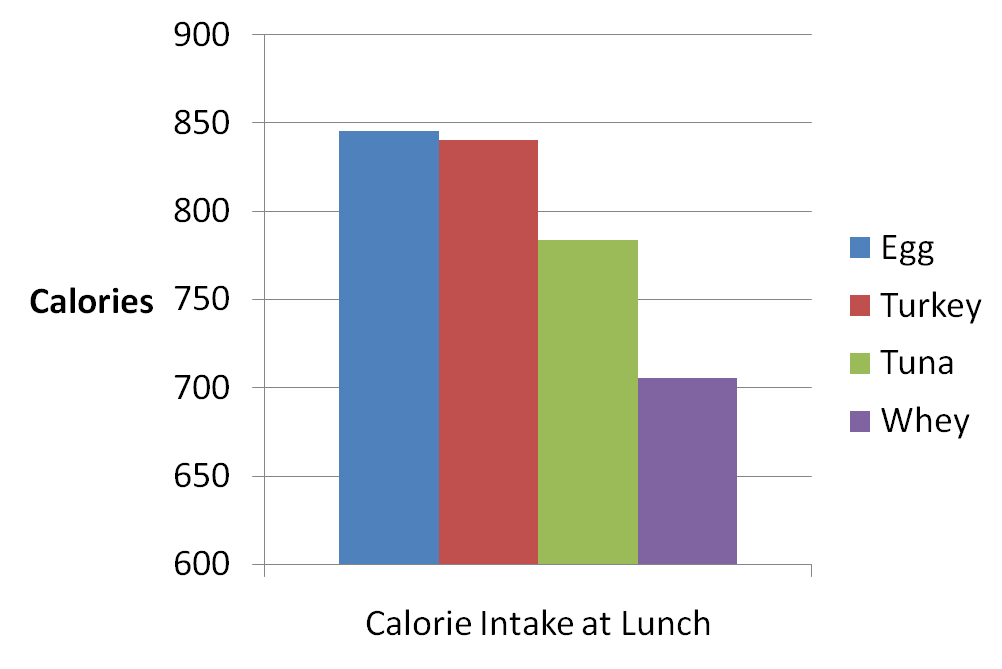

that compared the effects of 4 different types of protein on the

insulin response to a meal. This study was interesting because they

made milkshakes out of the different proteins (tuna shakes????

YUCK!!!!! Of course some people may remember the tuna shake recipes

from the misc.fitness.weights

days). The shakes contained only 11 grams of carbohydrate, and 51

grams of protein. Here's the insulin response to the different shakes:

You can see that all of these proteins produced an insulin response,

despite the fact that the carbohydrate in the shake was low. There was

also different insulin responses between the proteins, with whey

producing the highest insulin response.

Now, some might argue that the response is due to gluconeogenesis

(a process by which your liver converts protein to glucose). The

thought is that the protein will be converted to glucose, which will

then raise insulin levels. As I mentioned earlier, people will claim

that this will result in a much slower, more drawn-out insulin response,

since it takes time for your liver to turn protein into glucose.

However, that's not the case, because the insulin response was rapid,

peaking within 30 minutes and coming back down quickly at 60 minutes:

This rapid insulin response was not due to changes in blood glucose.

In fact, whey protein, which caused the greatest insulin response,

caused a drop in blood glucose:

The insulin response was associated with appetite suppression. In

fact, the whey protein, which had the highest insulin response, caused

the greatest suppression of appetite. Here's a chart showing the

calorie intake of the subjects when they ate lunch 4 hours after

drinking the shake:

The subjects ate nearly 150 calories less at lunch when they had whey

protein, which also caused the greatest insulin response. In fact,

there was an extremely strong inverse correlation between insulin and

food intake (a correlation of -0.93).

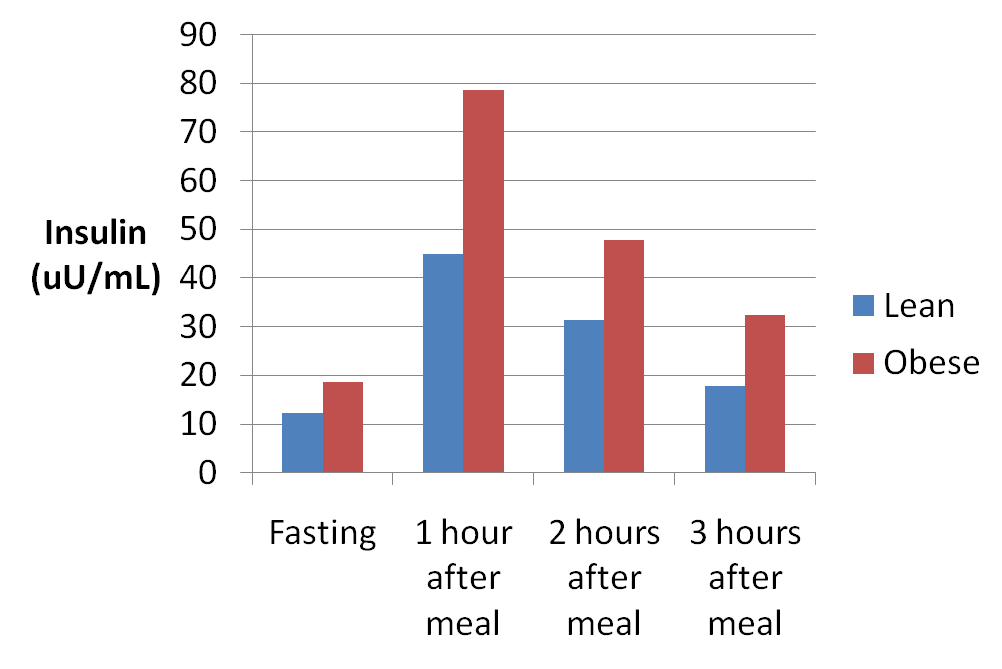

Here's data from another study

that looked at the insulin response to a meal that contained 485

calories, 102 grams of protein, 18 grams of carbohydrate, and almost no

fat:

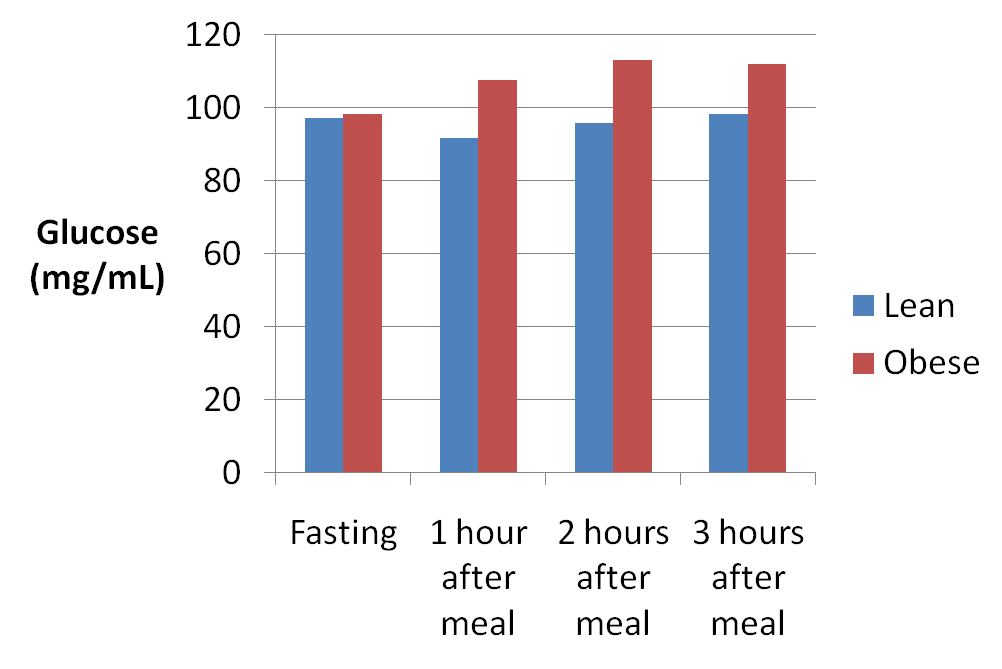

You can see that the insulin response was exaggerated in the obese

subjects, probably due to insulin resistance. Here's a chart of the

blood glucose response. You can see there was no relationship between

the glucose response and insulin, which was similar to the study

discussed earlier.

The fact is that protein is a potent stimulator of insulin secretion,

and this insulin secretion is not related to changes in blood sugar or

gluconeogenesis from the protein. In fact, one study found beef to stimulate just as much insulin secretion as brown rice.

The blood sugar response of 38 different foods could only explain 23%

of the variability in insulin secretion in this study. Thus, there's a

lot more that's behind insulin secretion than just carbohydrate.

So how can protein cause rapid rises in insulin, as shown in the whey

protein study earlier? Amino acids (the building blocks of protein)

can directly stimulate your pancreas to produce insulin, without having to be converted to glucose first. For example, the amino acid leucine directly stimulates pancreas cells to produce insulin, and there's a direct dose-response relationship (i.e., the more leucine, the more insulin is produced).

Some might say, "Well, sure, protein causes insulin secretion, but

this won't suppress fat-burning because it also causes glucagon

secretion, which counteracts insulin's effects." I mentioned earlier

how insulin will suppress lipolysis. Well, some people think that

glucagon increases lipolysis to cancel this out.

The thought that glucagon increases lipolysis is based on 3 things: the fact that human fat tissue has glucagon receptors, the fact that glucagon increases lipolysis in animals, and the fact that glucagon has been shown to increase lipolysis in human fat cells in vitro (in a cell culture). However, what happens in vitro isn't necessarily what happens in vivo (in your body). We have a case here where newer data has overturned old thinking. Research using modern techniques has shown that glucagon does not increase lipolysis in humans. Other research using the same techniques has shown similar results. I will also note that this research failed to find any lipolytic effect in vitro.

It should be remembered why glucagon is released in response to

protein in the first place. Since protein stimulates insulin secretion,

it would cause a rapid drop in blood glucose if no carbohydrate is

consumed with the protein. Glucagon prevents this rapid drop in blood

sugar by stimulating the liver to produce glucose.

Insulin: Not Such a Villain After All

The fact is that insulin is not this terrible, fat-producing hormone

that must be kept as low as possible. It is an important hormone for

appetite and blood sugar regulation. In fact, if you truly wanted to

keep insulin as low as possible, then you wouldn't eat a high protein

diet...you would eat a low protein, low carbohydrate, high fat diet.

However, I don't see anybody recommending that.

I'm sure some are having some cognitive dissonance reading this

article right now. I know because I experienced the same disbelief

years ago when I first discovered this paper

and how protein caused large insulin responses. At the time, I had the

same belief that others have...that insulin had to be kept under

control and as low as possible, and that spikes in insulin were a bad

thing. I had difficulty reconciling that study and my beliefs regarding

insulin. However, as time went on, and as I read more research, I

learned that my beliefs regarding insulin were simply wrong.

Now, you may be wondering why refined carbohydrates can be a

problem. Many people think it's due to the rapid spikes in insulin.

However, it's obviously not the insulin, because protein can cause rapid

spikes in insulin as well. One problem with refined carbohydrate is a

problem of energy density. With refined carbohydrate, it is easier to

pack a lot of calories into a small package. Not only that, but foods

with high energy density are often not as satiating as foods with low

energy density. In fact, when it comes to high-carbohydrate foods, energy density is a strong predictor of a food's ability to create satiety (i.e.,

low-energy density foods create more satiety). There are other issues

with refined carbohydrate as well that are beyond the scope of this

article.

The bottom line is that insulin doesn't deserve the bad reputation

it's been given. It's one of the main reasons why protein helps reduce

hunger. You will get insulin spikes even on a low-carb, high-protein

diet. Rather than worrying about insulin, you should worry about

whatever diet works the best for you in regards to satiety and

sustainability. As mentioned in last week's issue of Weightology Weekly,

individual responses to particular diets are highly variable and what

works for one person will not necessarily work for another. I will be

writing a post in the future on the need for individualized approaches

to nutrition.

Click here to read part 2 of this series on insulin.